Sizable infrastructure projects are neither rarely on time nor on budget. One combating solution by the public sector has been an increased usage of public-private partnerships (PPP, 3P or P3).

For contractors, a working knowledge of PPP should prove beneficial, as the frequency of this project structure is likely to spike with a potential $1 trillion infrastructure plan being discussed under a Trump administration.

In short, PPP typically involve a private entity financing, constructing and operating a public project in return for promised payments over the projected life of the project.

Payment can stem directly from the government in the form of tax credits or a project’s operating profits, or, indirectly from users, often via a toll, within the contract period that commonly can exceed 25 years.

Proponents of PPP believe the structure is the best model for major public projects because it imposes discipline on all players involved, with delays and cost overruns affecting everyone. Yet, entering into this partnership can be cumbersome if not executed with attention and proper education, or, if responsibilities are unbalanced between parties.

Pros and Cons

Pro: The private sector can provide better public services through improved efficiencies.

Con: PPP can become more expensive than publicly-managed projects. A PPP project might rely on a more-pricier private financing source instead of public bonds utilized by state agencies.

Pro: Creating economic diversification can make the country more competitive in facilitating its infrastructure base which boosts associated construction, equipment, and support services.

Con: The private partner faces availability and liability risk if unable to provide the operational or management services promised.

Pro: Private parties have a vested interest in the quality and success of the project because they will operate it for a lengthy period of time.

Con: PPP can evolve into monopolies motivated by rent-seeking behavior.

Swelling support

A potential $1 trillion Trump infrastructure plan could utilize repatriated corporate profits currently held overseas to put billions in the Federal Highway Trust Fund, which could potentially create a new U.S. investment bank with a $750 billion infrastructure fund available to state and local governments.

Dubbed a self-financing strategy that would produce a sizable volume of projects at no net cost to the government, the plan would offer private investors tax credits equivalent to 82 percent of the equity they commit on infrastructure.

The plan would rely on a new, direct federal revenue stream created by construction companies and their employees paying business and wage taxes into multi-year projects. The increased tax revenue is looked at to make up for the tax credits given to the private investors and pay for the remaining costs.

Opponents say such an infrastructure plan would help individual large projects reach completion but will not represent a cure-all to the nation’s infrastructure improvement need.

In addition to the proposed Trump plan, the U.S. Senate recently approved the Cross-Border Trade Enhancement Act of 2015, which encourages PPPs to improve border security and trade by making improvements at a land border port of entry subject to payment of a fee to reimburse the U.S. Custom Border Patrol for providing such services.

From coast-to-coast

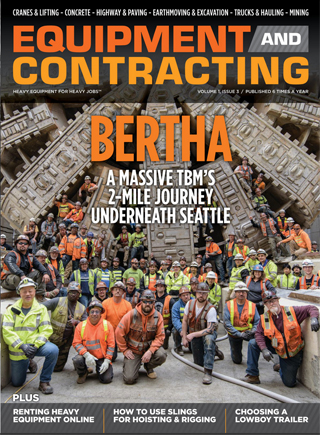

Transportation infrastructure projects are routinely built via PPPs, including highway, airports, railroads and tunnels.

This summer, construction started in Queens, New York City on a $4 billion project that will scrap LaGuardia Airport’s main terminal hub-and-spoke design, replacing it with two islands of gates connected to the main terminal building via pedestrian bridges.

LaGuardia Gateway Partners, a consortium of private companies including Skanska, will carry out the design and construction of the airport, operating and maintaining it through 2050. The private group is putting up $2.6 billion.

PPPs also are increasingly being used for public service projects involving school building, student dorms, prisons, entertainment and sports facilities.

At the University of California, Merced, the newest of the University California campuses, international developer Plenary Group has committed to a 39-year project that will cost more than $3.6 billion.

The Merced campus will double the university’s footprint, with Plenary standing to earn $1.77 billion over the 39-year span for design, construction and operation of the new buildings.

The progress and performance of these and other ongoing PPPs will serve as examples for what should be a wave of future partnerships, as the nation plans to significantly improve its infrastructure in the coming decades.

What is the primary source of payment for private entities involved in Public-Private Partnerships (PPP)?

Private entities in PPPs are typically compensated through payments from the government, tax credits, operating profits of the project, or tolls collected from users within the contract period.

What potential benefits and challenges are associated with Public-Private Partnerships (PPP)?

Pros include improved efficiencies, economic diversification, and vested private interest in project success, while cons may involve higher costs, reliance on expensive private financing, and the risk of PPP projects evolving into monopolies with rent-seeking behavior.