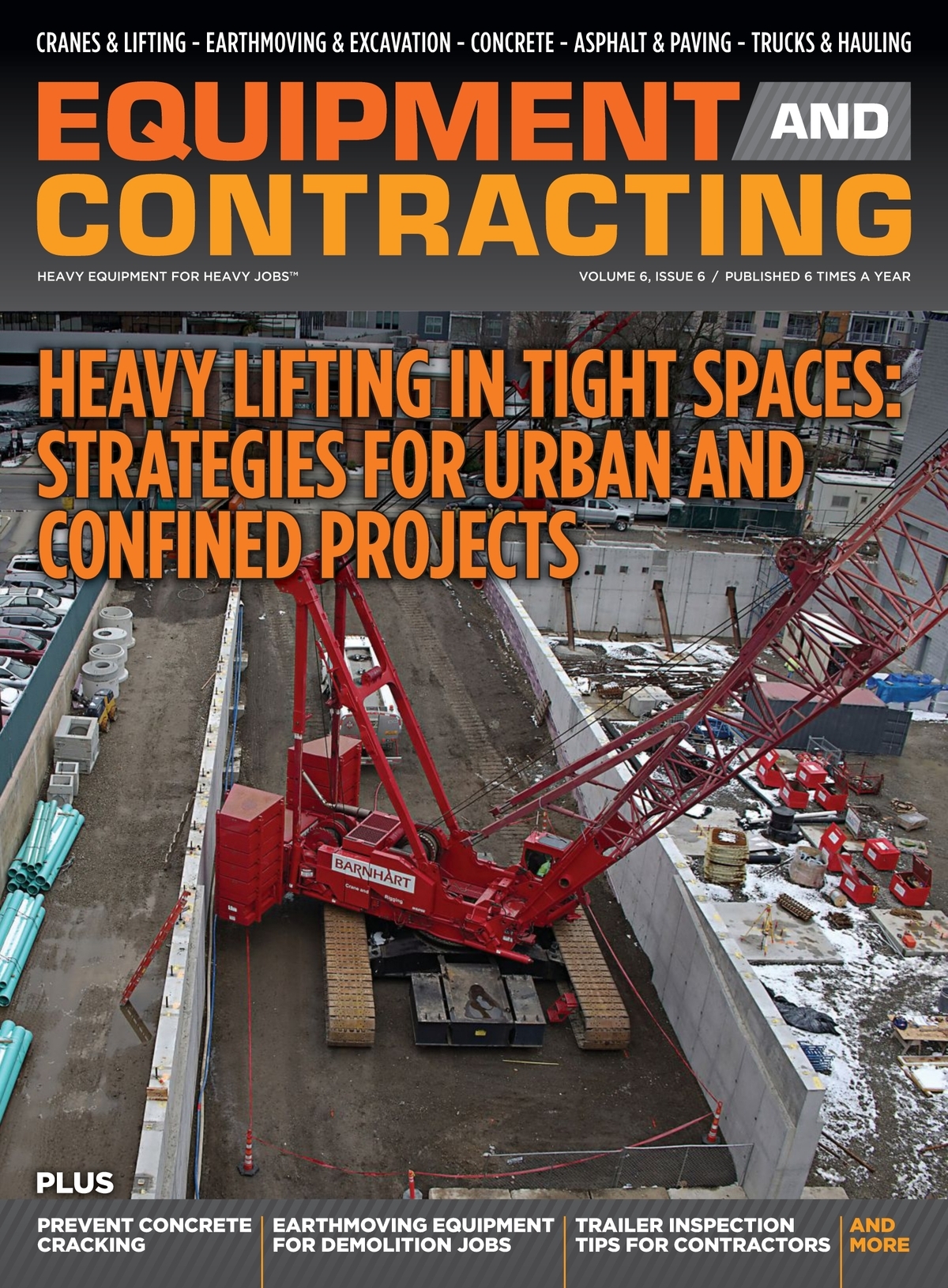

High-capacity crane lifts on marine, industrial, and heavy civil job sites demand more than equipment selection. They require disciplined engineering, clear communication, and strict adherence to established standards. As projects become more complex and lift weights increase, contractors are relying on engineered lift planning services to manage risk, protect personnel, and maintain schedule certainty.

On waterfront terminals, bridge projects, refinery expansions, and confined urban sites, high-capacity crane operations often qualify as critical lifts under OSHA definitions. OSHA 29 CFR 1926 Subpart CC identifies a critical lift as one exceeding 75 percent of the crane’s rated capacity or involving lifts of personnel, hazardous materials, or items that could cause significant damage if dropped. These conditions require formal planning, documented procedures, and qualified supervision.

Defining Critical Lifts in Complex Environments

A lift becomes complex when multiple variables interact. These variables include limited swing radius, proximity to existing structures, soft ground conditions, wind exposure, and coordination with other trades. On marine projects, additional factors such as tidal variation, barge movement, and corrosion exposure introduce further engineering considerations.

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers standard ASME B30.5 outlines operational and inspection requirements for mobile and locomotive cranes. The standard emphasizes pre-lift planning, load weight verification, and communication protocols. For contractors, this means lift plans must address not only crane capacity but also environmental conditions and site constraints.

Load Chart Interpretation and Capacity Calculations

Understanding crane load charts is foundational to lift planning. A crane’s rated capacity depends on boom length, boom angle, lift radius, counterweight configuration, and outrigger position. Capacity decreases as lift radius increases because the overturning moment grows relative to the stabilizing counterweight moment.

Lift radius is measured from the center of rotation to the center of gravity of the load. Even small increases in radius can significantly reduce allowable capacity. For this reason, lift radius and capacity calculations must be based on precise measurements rather than estimates.

Wind loading must also be considered, especially when lifting large surface area components such as precast panels, pipe racks, or modular assemblies. Manufacturers typically specify maximum allowable wind speeds for safe operation. Exceeding these limits increases side loading and dynamic forces on the boom.

Accurate load weight determination is equally critical. Engineering drawings, shipping documents, and manufacturer specifications should be used to verify total weight, including rigging gear. Rigging components such as slings, spreader bars, and shackles add to the total load and must be included in capacity calculations.

Ground Bearing Pressure and Crane Stability

Crane stability is governed by the relationship between applied load and ground bearing capacity. When outriggers are deployed, the load is transferred through outrigger pads into the soil. If ground bearing pressure exceeds soil capacity, settlement or failure can occur.

Geotechnical data, when available, should inform outrigger pad sizing and ground improvement measures. On marine and waterfront sites, soil conditions may vary significantly across short distances due to fill material, dredged sediments, or previous construction activity.

Ground protection systems such as timber mats or composite crane pads are often used to distribute loads over a wider area. The goal is to reduce contact pressure below the allowable soil bearing capacity. Calculating ground bearing pressure involves dividing the outrigger reaction force by the effective contact area of the support system.

For large crawler cranes, stability is influenced by track bearing pressure and crane configuration. Fully assembled crawler cranes exert distributed loads across their tracks, but assembly and disassembly phases may create higher localized pressures. Lift plans should address these transitional conditions.

Site Logistics and Multi-Trade Coordination

Complex job sites often require sequencing lifts around ongoing construction activities. In confined urban environments, crane swing paths must avoid adjacent buildings, utilities, and traffic corridors. Over water projects may require coordination between land-based cranes and barge-mounted cranes.

A comprehensive lift plan includes detailed site drawings showing crane position, swing radius, exclusion zones, and travel paths. These drawings help identify potential interferences and allow the project team to establish controlled access areas.

Communication protocols are equally important. ASME standards require the use of qualified signal persons and clear hand signals or radio communication. On noisy marine or industrial sites, radio communication with dedicated channels can reduce misunderstandings.

Weather monitoring procedures should also be integrated into lift planning. Wind speed, lightning risk, and visibility conditions affect crane operations. Establishing clear stop-work thresholds protects both personnel and equipment.

Risk Assessment and Mitigation Strategies

Formal risk assessment is central to high-capacity lifting. A lift-specific hazard analysis identifies potential failure modes such as rigging failure, structural instability, ground settlement, and mechanical malfunction. Each identified risk should have a corresponding mitigation measure.

Redundancy in rigging configurations may be used for critical components. Tag lines can control load rotation and reduce uncontrolled movement. Controlled lift speed and staged hoisting can limit dynamic effects.

Mechanical condition of the crane must be verified through inspection records. OSHA requires daily visual inspections and periodic documented inspections. Ensuring that hoist lines, sheaves, and braking systems are in proper condition reduces the likelihood of mechanical failure during heavy lifts.

Contractors frequently rely on specialized crane solutions when project complexity exceeds in-house capabilities. Access to experienced planners and operators supports compliance with regulatory requirements and reduces the probability of costly incidents.

Documentation and Engineering Review

Engineering lift plans should be documented and reviewed before execution. A typical lift plan includes load weight verification, crane configuration details, rigging specifications, ground condition analysis, and step-by-step execution procedures.

For critical lifts, third-party engineering review may be required by project owners or insurance providers. This review evaluates structural capacity of lift points, load path stability, and crane selection appropriateness.

Document control ensures that the latest revision of the lift plan is distributed to all relevant personnel. Pre-lift meetings provide an opportunity to review procedures, confirm roles, and address questions. Clear documentation also supports compliance audits and post-project evaluation.

Technology Integration in Lift Planning

Modern lift planning increasingly incorporates digital modeling. Three-dimensional lift simulations allow engineers to visualize boom movement, swing radius, and potential interferences before mobilization. These simulations can reduce uncertainty and improve positioning accuracy.

Load monitoring systems and rated capacity indicators provide real-time feedback to operators. While these systems enhance situational awareness, they do not replace proper engineering calculations. Operators must remain within rated capacities at all times.

Data collected from previous lifts can inform future planning. Recording ground conditions, wind impacts, and performance metrics helps refine assumptions and improve risk forecasting.

Building Confidence in High-Capacity Crane Operations

Engineering lift plans transform high-capacity lifting from a reactive activity into a controlled engineering process. By integrating accurate load calculations, ground stability analysis, regulatory compliance, and structured communication, contractors can execute complex lifts safely and efficiently.

As infrastructure and marine projects continue to grow in scale, the importance of high-capacity crane operations will only increase. Contractors that prioritize formal lift planning, risk assessment, and documented procedures are better positioned to manage liability and maintain productivity on demanding job sites.